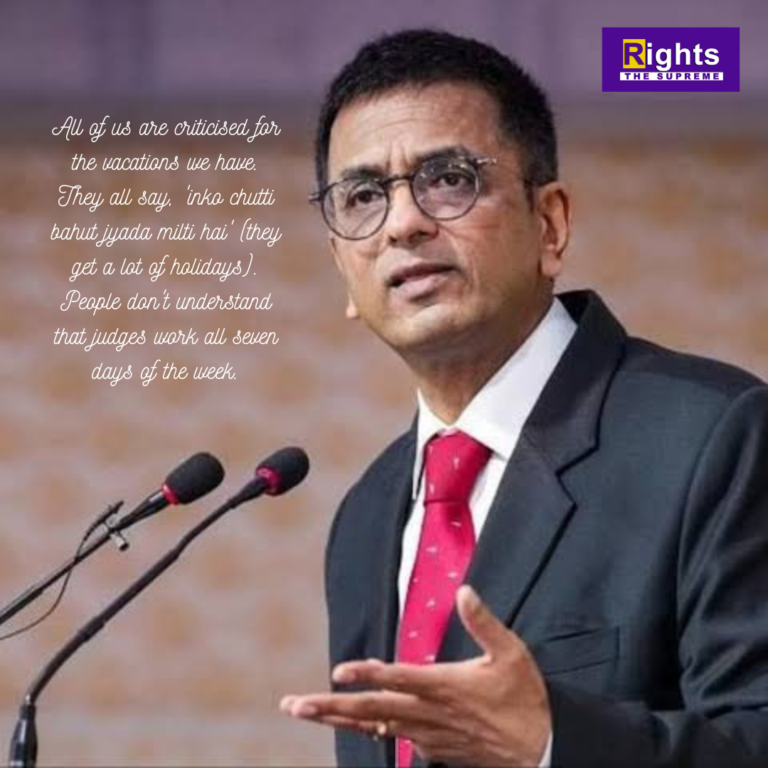

At a recent event in Prayagraj, CJI said- “All of us are criticised for the vacations we have. They all say, ‘inko chutti bahut jyada milti hai‘ (they get a lot of holidays). People don’t understand that judges work all seven days of the week. Our district judges work every single day, even on Saturdays and Sundays they have to do legal aid camps or they have to do other administrative work.”

The debate over the vacation days allotted to has come up repeatedly. In 2022, then Union Law Minister Kiren Rijiju said in Parliament that “there is a feeling among people of India that the long vacation which the courts obtain is not very convenient for justice-seekers”, and that it is his “obligation and duty to convey the message or sense of this House to the judiciary”.

What are court vacations?

The Supreme Court has 193 working days a year for its judicial functioning, while the High Courts function for approximately 210 days, and trial courts for 245 days. High Courts have the power to structure their calendars according to the service rules.

The Supreme Court breaks for its annual summer vacation which is typically for seven weeks — it starts at the end of May, and the court reopens in July. The court takes a week-long break each for Dussehra and Diwali, and two weeks at the end of December. While this judicial schedule has its origins in colonial practices, it has come under criticism for quite some time now.

What happens to important cases during court vacations?

Generally, a few judges are available to hear urgent cases even when the court is in recess. The combination of two or three judges, called “vacation benches”, hear important cases that cannot wait. Cases such as bail, eviction, etc. often find precedence in listing before vacation benches.

It Is not uncommon for courts to hear important cases during vacation. For example, in 2015, a five-judge Bench of the Supreme Court heard the challenge to the constitutional amendment setting up the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC) during the summer vacation. In 2017, a Constitution Bench led by then CJI J S Khehar held a six-day hearing in the case challenging the practice of triple talaq during summer vacation.

Why are court vacations criticised?

Like Rijiju said, extended frequent vacations are not good optics, especially in the light of the mounting pendency of cases and the snail’s pace of judicial proceedings. For an ordinary litigant, the vacation means further unavoidable delays in listing cases.

The colonial origins of the practice are not lost on the critics. The summer break perhaps began because European judges of the Federal Court of India found Indian summers too hot — and took the winter break for Christmas.

In 2000, the Justice Malimath Committee, set up to recommend reforms in the criminal justice system, suggested that the period of vacation should be reduced by 21 days, keeping in mind the long pendency of cases. It suggested that the Supreme Court work for 206 days, and High Courts for 231 days every year.

In its 230th report, the Law Commission of India headed by Justice A R Lakshmanan in 2009 called for reform in this system. “Considering the staggering arrears, vacations in the higher judiciary must be curtailed by at least 10 to 15 days and the court working hours should be extended by at least half an hour,” the report said.

In 2014, when the Supreme Court notified its new Rules, it said that the period of summer vacation shall not exceed seven weeks from the earlier 10-week period.

In the past, Chief Justices of India have tried to reform vacation cycles in view of the criticism.

In 2014, when the pendency of cases hit the 2 crore mark, then CJI R M Lodha had suggested keeping the Supreme Court, High Courts, and trial courts open round the year. CJI Lodha suggested that schedules of individual judges should be sought at the beginning of the year, and the calendar should be planned accordingly. With Justice Lodha’s tenure lasting just five months, that proposal did not see the light of the day.

Former CJI T S Thakur also suggested holding court during vacations if parties and lawyers mutually agreed. That proposal too, did not take effect.

What are the arguments in favour of court vacations?

Within the legal fraternity, the long breaks are strongly defended. Lawyers have often argued that in a profession that demands intellectual rigour and long working hours — both from lawyers and judges — vacations are much needed for rejuvenation.

Judges typically work for over 10 hours on a daily basis. Apart from the day’s work in court from 10:30 am to 4 pm, they also spend a few hours preparing for the next day. A frequently-made argument is that judges utilise the vacation to write judgments.

Another argument is that judges do not take leave of absence like other working professionals when the court is in session. In 2015, even after the Supreme Court heard a midnight plea against the execution of Yakub Memon, Justices Dipak Misra and Prafulla Pant returned to work the next morning. Family tragedies, health are rare exceptions, but judges rarely take the day off for social engagements.

Legal experts also point out that cutting down on court vacations will not see a dramatic decrease in pendency of cases, at least in the Supreme Court.

Data show that the Supreme Court roughly disposes of the same number of cases as are instituted before it in a calendar year. The issue of pendency relates largely to legacy cases that need to be tackled systemically. The argument that cutting the vacation period would be a solution to pendency is not backed by data, and takes away from real issues that contribute to the pendency problem.

What is the practice in other countries?

The Indian Supreme Court has the highest caseload among the apex courts around the world and also works the most. In terms of the number of judgments delivered too, with 34 judges, the Indian Supreme Court leads the way. In 2021, 29,739 cases were instituted before the Supreme Court, and 24,586 cases were disposed of by the court in the same year.

This year, between January 1 and December 16, the Supreme Court has delivered 1,255 judgments. This is apart from the usual workload of daily orders and hearings in cases where judgments are yet to be delivered.

By contrast, the US Supreme Court hears approximately 100-150 cases a year, and sits for oral arguments for five days a month. From October through December, arguments are heard during the first two weeks of each month and from January through April, arguments are heard in the last two weeks of each month.

In the UK, High Courts and Courts of Appeals sit for 185-190 days in a year. The Supreme Court sits in four sessions throughout the year, spanning roughly 250 days.